Small water utilities are navigating a far more complex landscape than a decade ago. Economic uncertainty, rapidly evolving technology, tighter regulations, workforce turnover, and climate-driven stressors are converging. These pressures are interconnected: aging infrastructure increases operational risk, insufficient funding impedes replacements, and staff shortages make it harder to maintain and modernize systems. To move from firefighting to stewardship, we must adopt a strategic, integrated approach that ties asset management, finance, workforce development, and technology together.

Critical context for 2026

Before we dig into the ten priority issues, it helps to see the environment in which utilities operate this year. Several cross-cutting forces will shape every decision we make.

- Economic uncertainty. Inflation and higher construction and materials costs make capital projects more expensive. Household budgets are constrained, which raises political sensitivity around rate increases even when they’re necessary.

- Technological demands. Smart meters, AI-driven analytics, and remote monitoring create major opportunities to reduce non-revenue water and optimize operations but also add operational complexity and cybersecurity risk.

- Escalating regulation. Lead and copper rule revisions, emerging contaminant standards such as proposed PFAS limits, and new monitoring and reporting requirements raise compliance costs and technical demands for small systems.

- Climate impacts. Extreme weather, prolonged droughts, and changing precipitation patterns disrupt sources, damage infrastructure, and increase variability in supply.

- Limited resources. Most small utilities face constrained budgets and small staffs. That amplifies the effect of every other challenge and makes prioritization essential.

All of these interact. Asset decisions affect finance. Workforce capacity determines whether technology delivers value. Regulation affects capital planning. Seeing those links is the first step toward practical solutions.

The top 10 priority issues—and concrete responses

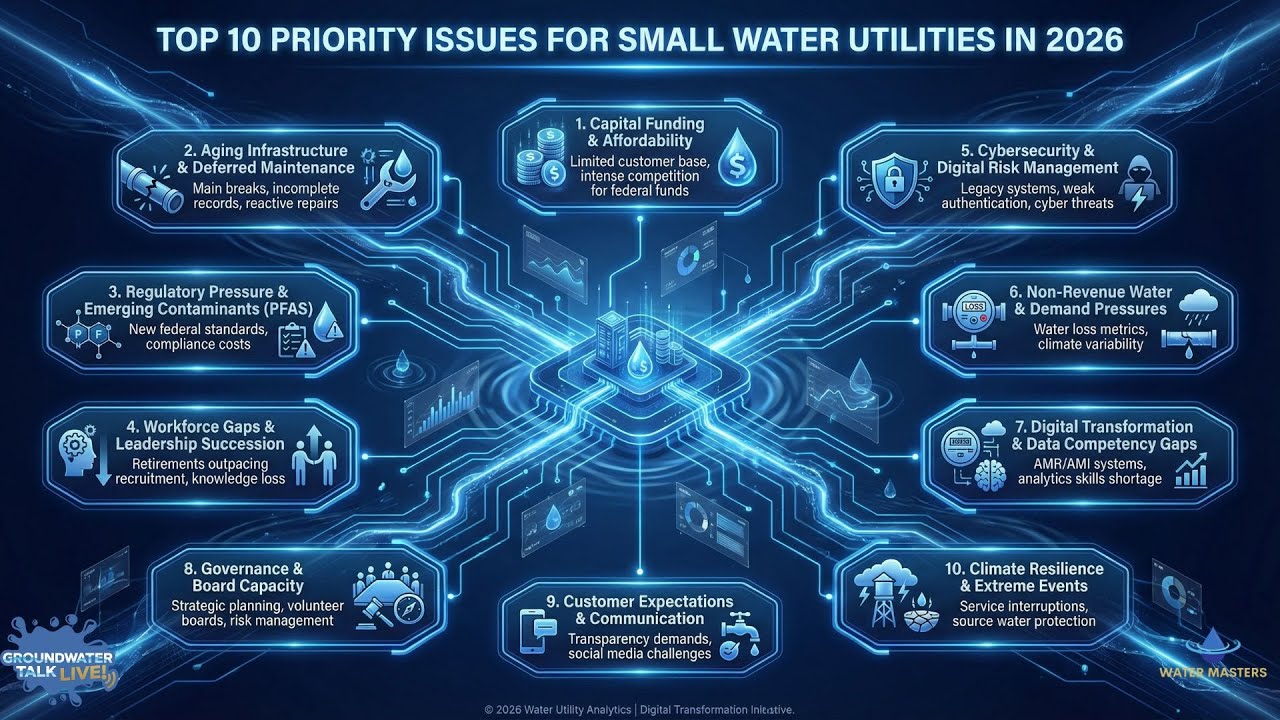

We list the priorities below in the order they most often dictate decision-making for small systems. Each item includes what to watch for, why it matters, and a short action checklist you can put to work immediately.

1. Aging infrastructure crisis

Many distribution mains, pump stations, valves, and treatment components are operating well beyond their design life. The average age of water mains in the U.S. exceeds 45 years, and some systems run pipes that are more than 100 years old. Deferred maintenance creates a cycle of emergency repairs and customer interruptions.

Why it matters:

- Higher frequency of breaks and leaks.

- Increased emergency repair costs and service outages.

- Greater risk of regulatory violations and public complaints.

Practical actions:

- Create and maintain an asset inventory. Identify pipes, pumps, valves, tanks, treatment trains, and the expected life of each.

- Conduct condition assessments. Use in-field inspections, leak histories, and manufacturer data to prioritize replacements.

- Build a rolling capital improvement plan (CIP). Map replacements over a 10- to 15-year horizon so projects aren’t surprises.

- Track key performance indicators (KPIs). Breaks per 100 miles, unplanned outage hours, and non-revenue water percentage help quantify risk and spend.

2. Capital funding gap

EPA estimates the U.S. needs about $680 billion for drinking water infrastructure over the next 20 years. That funding gap is especially acute for small systems that rely on state revolving funds, low-interest loans, occasional grants, and limited rate revenue.

Why it matters:

- Capital projects are delayed or downsized without funding.

- Loans require administrative work and sometimes matching funds that small systems struggle to provide.

- Competition for federal and state dollars is increasing as big programs mature.

Practical actions:

- Map needs to sources. Link each CIP item to likely funding sources: SRF, USDA Rural Development (RUS), state/tribal grants, and any remaining IIJA/ARPA programs.

- Prioritize “shovel-ready” projects. Fundability improves when planning, environmental review, and permitting are complete.

- Invest in administrative capacity. If grant writing or SRF application rules are a blocker, partner with consultants or regional technical assistance providers.

- Explore phased projects. Break large replacements into manageable phases to match available funds.

3. Asset management deficiency

Many utilities lack a mature asset management program. Without it, prioritization and financial justification become guesswork. Asset management is the connective tissue between infrastructure needs and financial planning.

Why it matters:

- Reactive maintenance costs far more than proactive or predictive maintenance.

- Deficient AMPs make it hard to secure funding because applicants can’t demonstrate need and readiness.

- Utilities lose the opportunity to optimize life-cycle costs and performance.

Core components of a functional AMP:

- Asset inventory with location (GIS) and key attributes.

- Condition assessment and remaining useful life estimates.

- Risk prioritization linking consequence and probability of failure.

- 10–15 year CIP tied to realistic financing scenarios.

- Performance monitoring through KPIs and dashboards.

Quick wins:

- Start with a four-week AMP sprint: inventory high-value assets, assign condition categories, and draft a CIP outline.

- Use GIS even at a basic level—locational data makes planning and grant packaging faster.

- Document the AMP process so future board members or staff can continue it.

4. Workforce development crisis

Nearly 40 percent of operators in small systems are over age 55. The so-called silver tsunami threatens both capacity and institutional knowledge. When experienced staff retire we risk losing procedural know-how, troubleshooting skills, and relationships with regulators and vendors.

Why it matters:

- Operational errors and service interruptions rise when inexperienced staff fill gaps.

- High turnover increases training costs and service risk.

- Recruiting technical staff in small towns is competitive.

Practical actions:

- Run a compensation benchmark. Compare salaries to neighboring systems and adjust to be competitive.

- Launch apprenticeships and training partnerships. Partner with your state rural water association or community colleges for structured pipelines.

- Create knowledge-capture programs. Write SOPs, video key procedures, and use checklists so departures don’t erase institutional memory.

- Mentorship and cross-training. Encourage senior staff to mentor newer hires and rotate responsibilities to widen skillsets.

- Engage high schools and career tech programs. Build pipeline awareness for trade careers that lead to long-term utility employment.

5. Regulatory compliance burden

Regulatory timelines are tightening and sampling and reporting requirements are increasing. Lead and copper rule revisions and proposed PFAS maximum contaminant limits are shifting what systems must do to remain compliant.

Why it matters:

- Compliance can require upgrades that exceed the budget and technical capacity of small systems.

- New sampling schedules and inventories are administratively intensive.

- Failure to comply risks enforcement, fines, and public trust loss.

Practical actions:

- Inventory exposures. Know your service line materials, sampling sites, and the vulnerable populations you serve.

- Plan for phased compliance. Where full immediate replacement is infeasible, document interim control measures and timelines.

- Leverage technical assistance. State primacy agencies, rural water associations, and third-party labs can advise on sampling plans and treatment options.

- Budget and communicate. Include compliance costs in your CIP and explain them to customers so rate actions are understandable.

6. Cybersecurity vulnerabilities

As small systems adopt SCADA, cloud platforms, and remote telemetry, cybersecurity rapidly becomes an operational safety issue. Small utilities are attractive targets because they often lack basic defenses.

Primary vulnerabilities:

- Unsecured SCADA systems exposed to the internet without firewalls or access control.

- Default credentials, unpatched systems, and outdated software.

- Human risk such as phishing and social engineering.

Consequences include service disruption, loss of control over chemical dosing, potential contamination events, and ransomware. Basic cybersecurity investments can prevent these scenarios.

First-line defenses:

- Conduct a cyber risk assessment. Free tools are available from EPA, AWWA, DHS, and WaterISAC.

- Change default passwords and require strong password policies.

- Implement multi-factor authentication. Particularly for remote access.

- Network segmentation and firewalls. Keep SCADA on a separate network with strict access controls.

- Regular patching and updates. Schedule maintenance windows to apply security updates.

- Train staff on phishing and social engineering. Regular drills and refreshers reduce human risk.

- Back up critical data offline. Ensure backups are isolated from networks that could be encrypted by ransomware.

7. Water scarcity and quality challenges

Some regions are experiencing prolonged drought, source depletion, and increasing contaminant loads. PFAS and other emerging contaminants also force utilities to reconsider sources and treatment strategies.

Why it matters:

- Supply disruptions require demand management and alternative sourcing.

- Treatment for contaminants is often capital intensive and technically demanding.

- Public concern about water quality can drive political and legal pressure.

Practical actions:

- Conduct source vulnerability assessments. Understand the risks for every supply and the contingency options.

- Implement water loss control. Leak detection campaigns and advanced metering lower demand and keep more water in billable use.

- Prepare treatment alternatives. For emerging contaminants, evaluate granular activated carbon, ion exchange, and other technologies with realistic cost estimates.

- Engage stakeholders. Farmers, industry, and municipalities can be partners in conservation and source protection.

8. Rate setting and affordability balance

Raising rates is politically sensitive, but underpricing water leads to deferred maintenance and eventual service breakdowns. The trick is a fair, transparent approach that balances financial sustainability and customer affordability.

Why it matters:

- Insufficient revenue hinders capital projects and maintenance and increases long-term costs.

- Sudden spikes in rates lead to public backlash; predictable, modest annual adjustments are often easier to accept.

- Low-income customers must be protected through targeted assistance programs.

Practical actions:

- Perform a rate study every 3 to 5 years. Update your assumptions and test rate options.

- Consider annual adjustments tied to CPI or a set percentage. Predictability makes planning easier and minimizes shock.

- Design affordability programs. Lifeline rates, bill discounts, or payment plans for qualifying households.

- Communicate transparently. Explain what the rates buy—clean water, treatment, emergency readiness—and the costs of inaction.

9. Climate resilience planning

Few small systems have formal adaptation plans even though extreme weather and shifting hydrology are increasingly likely. Resilience reduces disruption and speeds recovery after events.

Why it matters:

- Infrastructure designed for old climate norms may not survive more intense storms or drought cycles.

- Unplanned damage increases emergency repair spend and reduces service reliability.

- Community trust erodes when outages become frequent.

Practical actions:

- Complete a vulnerability assessment. Identify critical assets at risk from floods, droughts, wildfire, and storms.

- Design adaptation measures. Options include redundant sources, elevated controls, hardened pump stations, and flood-proofing critical equipment.

- Integrate resilience into the CIP. Prioritize projects that reduce climate risk and protect essential services.

10. Public engagement and trust

Public support underpins rate approvals, grant applications, and long-term investments. Engaged communities are more likely to back necessary changes and conservation efforts.

Why it matters:

- Poor communication breeds suspicion and opposition to rate increases and projects.

- Transparent engagement reduces delays in project approvals and eases political hurdles.

- Community education can reduce demand and improve source protection.

Practical actions:

- Create a communication plan. Regular newsletters, social media updates, and public meetings focused on service performance and finances.

- Host plant tours and school outreach. People respect systems they understand.

- Be proactive before rate requests. Explain the link between rates, infrastructure health, and reliability—show the AMP and CIP summaries.

- Offer participation avenues. Stakeholder committees or customer advisory groups can provide meaningful input and build buy‑in.

Strategic foundation: three pillars to guide decisions

To navigate these priorities we recommend organizing strategy around three pillars: financial discipline, technology adoption, and strategic collaboration. These address funding, operational efficiency, and capacity to implement change.

Financial discipline

- Regular rate studies (3–5 years) and transparent rate-setting policies.

- Reserve policies—maintain operating reserves equal to 10–15 percent of operating expenses to handle emergencies.

- 10–15 year CIP integrated with the AMP and linked to funding timelines.

- Spend discipline and lifecycle costing to prioritize the highest-impact investments.

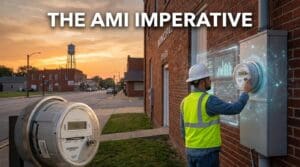

Technology adoption

- GIS for asset location and condition tracking.

- Advanced metering infrastructure (AMR/AMI) to understand consumption and detect leaks.

- Cloud-based asset management platforms for records, work orders, and performance dashboards.

- Cybersecurity foundations—network segmentation, MFA, and staff training.

Strategic collaboration

- Regional partnerships and mutual aid agreements for emergency response.

- Technical assistance relationships with rural water associations, state agencies, and nonprofit organizations.

- Shared procurement and bulk purchasing agreements to lower unit costs for meters, chemicals, and equipment.

- Coalitions for grant applications and lobbying to increase the chance of funding success.

Immediate action framework: a practical timeline

To shift from reactive to proactive management, start with a near-term action plan that can be implemented with modest staff time and reasonable expense.

First 90 days

- Assess current state. Compile a baseline: AMP existence and maturity, CIP, reserves, rate study recency, staffing plan, and cybersecurity posture.

- Secure quick wins. Fix default passwords, initiate basic staff cyber training, and document 3 critical SOPs.

- Start a basic GIS inventory. Prioritize mains, hydrants, tanks, and pump stations.

- Run a one-page financial summary for the board. Show operating reserves, debt, and critical near-term CIP items.

6–12 months

- Develop or update AMP and CIP. Do condition assessments and map replacements for the next 10–15 years.

- Perform a rate study. Set a financial path to fund the CIP and to build reserves.

- Launch an apprenticeship/mentorship plan. Partner with the local rural water association or community college.

- Begin phased technology adoption. Pilot AMI for a subset of customers or deploy a leak detection survey.

- Complete a cyber risk assessment. Use EPA, AWWA, or DHS tools and implement the top three remediation items identified.

1–3 years

- Execute prioritized CIP projects. Use a mix of SRF loans, grants, and rate revenue.

- Fully implement AMI and GIS integration. Tie meters to billing and loss detection dashboards.

- Institutionalize workforce development. Full apprenticeship pipeline and succession planning in place.

- Achieve basic cyber hygiene. Firewalls, network segmentation, MFA, and regular training implemented.

- Establish resilience projects. Harden critical facilities and secure backup source options where feasible.

KPIs and dashboards: what to measure

A concise dashboard helps boards and managers see system health at a glance. Focus on a small set of leading indicators rather than dozens of metrics.

- Non-revenue water (NRW) percentage — goal: reduce year-over-year.

- Breaks per 100 miles — tracks distribution system integrity.

- Unplanned outage hours — quantifies service reliability.

- Customer complaints per 1,000 accounts — measures satisfaction and quality perception.

- Capital project delivery — percent on schedule and budget.

- Operating reserve level — percent of target (e.g., 10–15%).

- Staff vacancies and training hours — workforce health indicators.

- Cybersecurity incidents and patch compliance — operational security indicators.

Funding sources and application tips

Common funding avenues for small utilities include state revolving funds (SRF), USDA Rural Development (RUS) programs, state grants, regional economic development funds, and occasional federal stimulus programs. We note a few practical tips:

- Prepare documentation in advance. Lenders and grantors expect an AMP, CIP, environmental review, and financial statements.

- Timing matters. Funding cycles can take months. Start applications early and track deadlines.

- Consider phased funding. If a full replacement is unaffordable, phase construction and apply for tiered assistance.

- Leverage technical assistance. Regional providers can prepare grant-ready packages and navigate SRF rules.

- Build consortiums. Joint applications with neighboring utilities can increase competitiveness for regional projects.

Workforce, SOPs, and knowledge capture

Retirements take institutional knowledge with them. Making that information durable is essential.

- Document standard operating procedures. A well-organized SOP library should include startup/shutdown, treatment adjustments, permit reporting, safety procedures, and emergency steps.

- Use multimedia capture. Short videos of hands-on tasks, annotated photos, and equipment manuals speed up training.

- Implement shadowing and mentorship. Pair new hires with senior operators for at least 6 months of guided practice.

- Cross-train staff. Avoid single points of failure by ensuring multiple people can perform critical tasks.

Cybersecurity: a practical checklist

Start with simple, high-impact controls:

- Change default passwords and require complex password policies.

- Enable multi-factor authentication for remote systems and administrative accounts.

- Segment SCADA and operations networks from corporate and guest networks.

- Install and maintain firewalls and intrusion detection on remote access points.

- Apply security updates on operating systems and critical applications in a timely manner.

- Back up control systems and billing data offline and test recovery procedures.

- Train staff on phishing and social engineering—schedule annual refreshers.

- Run tabletop incident response exercises with staff and vendors.

Technology adoption: where to get real ROI

Not every new gadget is the right fit. Prioritize technology that delivers measurable operational and financial returns.

- AMR/AMI: Smart meters reduce reading costs, improve billing accuracy, and detect leaks faster. A targeted deployment for high-leak or high-consumption areas is a smart first step.

- Leak detection and pressure management: These interventions can significantly reduce non-revenue water.

- GIS: A basic GIS tied to your AMP dramatically reduces time to locate assets and supports grant applications.

- Cloud-based asset management platforms: Use them for work orders, inventory, warranties, and KPIs. Cloud platforms reduce IT overhead.

- Remote monitoring for critical assets: Pumps and chemical feed systems benefit from alarms and telemetry.

Public engagement: communication playbook

Build trust long before you ask for a rate increase or start a disruptive project.

- Regular transparency: Issue a quarterly service and finance summary to all customers.

- Tell the story: Explain how rates fund safety, compliance, and reliability. Use simple numbers and real examples.

- Engage locally: Offer tours, attend chamber events, and visit schools to connect the system to everyday life.

- Provide assistance: Make low-income or hardship bill programs visible and easy to access.

- Use clear messaging around projects: Explain timelines, benefits, alternatives, and impacts before work starts.

Governance and accountability

Boards and managers must align around a few core governance practices to sustain progress:

- Require an AMP and CIP as part of annual planning.

- Adopt financial reserve and debt policies.

- Require regular KPI reporting with a simple dashboard for board review.

- Approve a workforce development plan and cybersecurity policy with assigned responsibilities.

- Make engagement a standing agenda item so the public-facing narrative stays current.

Measuring success: when have we won?

We know we are moving in the right direction when:

- Emergency repair spending declines and preventive maintenance rises.

- Non-revenue water is reduced and metering accuracy improves.

- The CIP is funded and projects proceed on schedule.

- Key positions are filled, training is documented, and staff turn over less frequently.

- Cybersecurity assessments show improved posture with routine patching, MFA, and staff training in place.

- Public trust indicators—like fewer complaints and easier rate approvals—improve.

Next steps we can take together

Three actions that produce disproportionate benefits:

- Commit to proactive asset management and long-term financial planning. Good planning reduces emergency spending and increases access to funding.

- Invest in workforce and cybersecurity. People and safe operations are the backbone of every system.

- Pursue partnerships and external funding now. Grants and low-interest loans require preparation—start early so you aren’t sidelined by application timelines.

If you don’t yet have an AMP, start small: inventory the highest-value assets, assess their condition, and draft a 10-year CIP. If cybersecurity feels overwhelming, run a free assessment from EPA, AWWA, or your state primacy agency and implement the top three fixes immediately.

Closing thoughts

The challenges for small water utilities in 2026 are real, but they are manageable with disciplined planning, smart technology choices, workforce investment, and community engagement. The work is cumulative: an AMP feeds the CIP; the CIP informs funding strategy; funding pays for technology and workforce development; and all of it supports safe, reliable service.

Start with the basics, plan for the future, and lean on partnerships. The transition from reactive crisis management to proactive stewardship is not instantaneous, but it is achievable—and the sooner we act, the more options we preserve for our communities.

Resources and tools

Useful starting points and organizations:

- EPA asset management and cybersecurity guidance

- AWWA assessment tools and best practices

- WaterISAC cyber resources and alerts

- State rural water associations and USDA Rural Development offices

- Regional technical assistance providers and mutual aid networks

Want help building an AMP?

For teams that need a structured path, consider a short cohort approach: a focused 3–4 week program that produces a usable AMP outline, priority CIP items, and a set of KPIs you can start tracking. That structured support dramatically reduces the time to get a plan ready for funding applications and board adoption.

Tackle the priorities in sequence, but remember they are linked. Address asset management early and it becomes the framework for everything else. Invest in people and cybersecurity, and the system’s capacity to deliver safe water improves substantially. And keep the community informed—trust is the tidy margin that makes everything else possible.